Stephen T. Asma, a professor of philosophy at Columbia College, took up monsters by way of natural history museums, the subject of his last book, where he found “anything from pickled fetuses in jars to bizarre twinning, things with two heads.” His latest book, On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, takes on a subject timely not just because of Halloween, but also because of the vampires and zombies appearing everywhere in popular culture. “Vampires are always sort of charming and upper class, and they’re kind of hot,” Asma said, explaining our dual fascination. “Zombies really represent the lowest common denominator. We’re in the middle of these two classes – we have bourgouis desires to be vampires, and we want to avoid the proletarian monsters, the zombies.” Below, he analyzes for Zócalo some lesser-known monsters and monster myths, and explains why we’re still afraid.

Q. You and I have the same fear – murky waters, and what could be inside. I’m wondering where our fear of monsters comes from, and how much of it is universal?

A. We have certain kinds of stories and images that are really frightening everywhere, especially in pictorial traditions. You see these repetitions of certain creatures that are frightening – mixtures of two different kinds of animals for examples, or things based on wolves, or things based on sea creatures like the octopus and the squid. There is a culture of monsters that is hugely influential. But I actually think that there is a deeper biology of monster fears and phobias that we are only just starting to understand. My own view is we’ll get a lot of light on this in the next couple of decades. We’re getting better at understanding how the brain evolved. We know for example that we can describe the brain as having three structures. The oldest and earliest would be the reptile brain. Built on top of the reptile brain is the limbic system, where a lot of emotions occur. On top of that is the neocortex, the more rational part of the brain.

My own view is that monsters come out of the limbic system, that we evolved certain kinds of fears that were beneficial for our survival. As we’ve gotten smarter and more civilized, we’ve used those original phobias and made a whole culture of monsters. For example, you and I are afraid of the water, and I have a feeling there’s a good reason why our ancestors developed a fear of water they couldn’t see in – because real predators could be in there. There may be similar reasons why people are afraid of spiders or creepy crawly things, because on the African savannah where Homo Sapiens originally evolved, there are several species of poisonous spiders. You can imagine that if you develop some kind of phobia about them, you would survive and live to procreate. It’s speculative, but it makes sense, I think.

There are a lot of universals in monsters, across racial, ethnic, and geographic spreads, but probably the more familiar parts of monster lore has a cultural face to it. People from Northern Europe tended to have monsters that were based on wolves. You wouldn’t find monsters based on wolves in sub-Saharan Africa.

Q. Given that we are getting smarter and more civilized, why are we still afraid? And what are we afraid of today?

A. There are a lot of things we know we shouldn’t be afraid of, but we are still afraid. That’s why I mentioned the limbic system. For example, we know that you can have a phobia about snakes. Psychologists have done studies on this – they’ll take people who are snake-phobic and show them a snake. Then they’ll remove the poison ducts and even the teeth of the snake, so there is no way for the snakes to poison or bite the snake-phobic people, but they will still freak out. What that indicates to some is that no matter how smart you get, there are certain fears that are down in this subcortical region. I tend to think that’s probably true.

There’s definitely room to wiggle, though, and educate ourselves and fix some bad tendencies. I looked at the history of monsters and you see often that what human beings are most afraid of are other human beings that they are not familiar with – xenophobia. If you look at the ancient Greeks, the medieval period, right up into the scientific age, you will see a lot of demonizing of other people, literally demonizing them. They’ll be shown as having horns and a tail, people will say “They’re not like us and therefore we are justified in being hostile toward them.” That’s the kind of thing we can do better on. We should try to avoid this natural tendency to demonize people who are different from us, we should try to de-monster them.

Q. De-monster, that’s an interesting word. What about the word monster – where does it come from, and is it always negative?

A. The word originally is from the Latin, monstrum. I’ve seen different etymologies of it. Some relate it to the word monere which means to warn. The original Latin phrase refers to some kind of warning of future events – a bad omen, basically. It could be a good omen, too, but it is usually pejorative. The word evolved to refer originally to babies born with developmental disabilities. The Greeks didn’t understand why it happened; they thought this was a message from the fates. There are even cases where some high ranking military officials were told by priests of the birth of a deformed child – they would use it to argue against a particular military campaign.

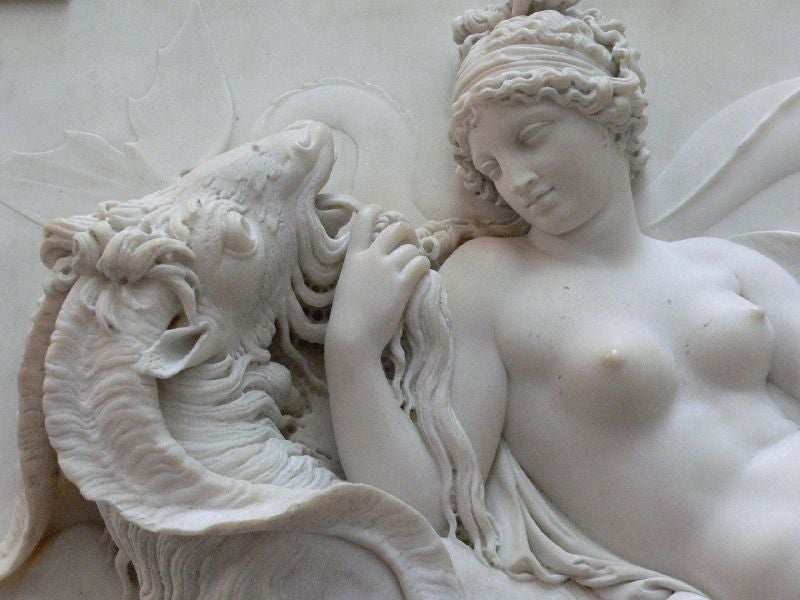

The word was also used, in early Greek and Roman civilizations, to refer to what we now call mythical races. They really believed they were out there. Greeks and Romans believe there were species of monsters in India and African – the Blemmyae, which had no head, and had its face in its chest. There was a literature about them. The Cyclops is another example, the griffin. There are even some funny ones – these monsters who have one leg and a giant foot at the bottom and they hop around. Those were believed in from the 5th century BC to the Renaissance. In the adventure literature that came with the discovery of the New World, they’re always asking: did you see the Blemmyae? or the Cynocephalus or dog-headed race? The monsters were often these natural creatures that were bizarre.

There’s another use of monster that is more theological – demons who possess you, witches. That is a different monster tradition. There are freaks, which come back strong during the P.T. Barnum era, when they’re celebrated as being unique and strange and wonderful. There is a terrible history of exploitation, there, too.

Now we talk about monsters being psychopaths and criminals. But they have some of the same qualities of the older monsters – they’re hard to understand, they’re irrational, unmanageable. They represent really deep vulnerabilities.

Q. What about fears of monsters that relate to new technologies and science, like robots and aliens? Are these fears new in any way?

A. There are probably some really new aspects because the technology is new. The fact that we can get into the genome and actually manipulate it is something that simply didn’t occur before. But all of the Frankenstein stuff is there. Many people who are afraid of new technology, who are sort of Luddites, would identify with this Romantic vision, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, that human beings should not play god, and scientific and technological advancements in some of these directions is too frightening and unethical. For those reasons, new technology fears draw on a lot of the old monster fears – that you’re going to create something you can turn on, but you can’t turn off again. you see this in the idea that robots will have a revolution, or artificial intelligence in the form of computers that will turn against us. There are tons of great science fiction monster narratives like this. It’s not that different from Frankenstein, or the older Jewish legend of the Golem. You turn it on to help you, but it takes on a life of its own, it can’t be controlled, and it turns on you and kills you. The new technological phobias are tapping into an old tradition.

Q. I’m curious about the flip side of the monster myth-the hero. Is there always a hero, and how do we relate to them?

A. I wouldn’t say it’s a necessary connection, but whenever you see a good monster story there is some hero component. I’m a bit of a Freudian with monster movies and monster stories. You get to go on this little holiday to the id, to where the wild things are. You see the monster acting without social constraints and conventions, and engaging in this aggressive bloodbath. There is something deeply satisfying about that for many people, which is why monster movies do so well at the box office. But ultimately order has to be restored. You need to have some hero component. You need Ripley in the Alien series to finally get the lid back on the jar. In most monster stories, the hero phase is really important, because people don’t want to be left in a phase of paranoid insecurity, with the feeling that I could get bitten by a vampire at any moment, or contract some monstrous disease. I think we want to see in our art that we have some resources to beat back the enemy, that we do have some way of getting control over the chaos and protecting what’s valuable to us. The hero is always lurking, waiting to come onstage after we’ve had our thrill. We need somebody to shoot the zombies in the head.

Q. Are heroes mostly men, and if so, why?

A. There are often female heroes, like Ripley, but they are harder to find. I don’t know if that’s because of a culture that says violent, militaristic solutions are masculine, so therefore you can’t have many women doing it in films and literature. Rightly or wrongly, there is that association in popular culture. The way to meet a monster enemy is not with diplomacy and negotiation. I think that’s really part of what the monster represents – you can’t talk them out of their rampage. The only way to meet this kind of enemy is with aggression. And for whatever reason, aggressive solutions are masculine. Some people celebrate this, others criticize it, saying there are too many men running around with guns trying to clean up the Old West. I don’t take a position, I just notice it.

Q. You mentioned diplomacy and negotiation, which brings up the question, how often do we describe political enemies as monsters? Or is it just too strong of a word?

A. Today we do call psychopathic killers “monsters” – every day there is some new use of that epithet to refer to some heinous crime. But I was noticing as I was writing that there is a harder-to-locate, diffuse notion of monster-the idea of a monstrous civilization, or a monstrous society or political ideology. You can see it cropping up, though it is a little harder to see than in the cases of individual psychopaths. There are people on the conservative side who will, say, look at Islam. I don’t agree with this view, but people like Christopher Hitchens or Ayaan Hirsi Ali will claim Islam itself is a monstrous ideology. On the other side, people look at the West and say, the West is a monstrous society, which allows for unrestrained sexual immodesty, and produces monstrous behavior. We’re still monstering each other across the divide, but it’s not that there is something wrong with the brain, or a demon possession. They’re claiming a culture is morally monstrous and it churns out monsters.

*Photo of Stephen Asma by Brian Wingert. Photo of Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster courtesy mharrsch.

Send A Letter To the Editors