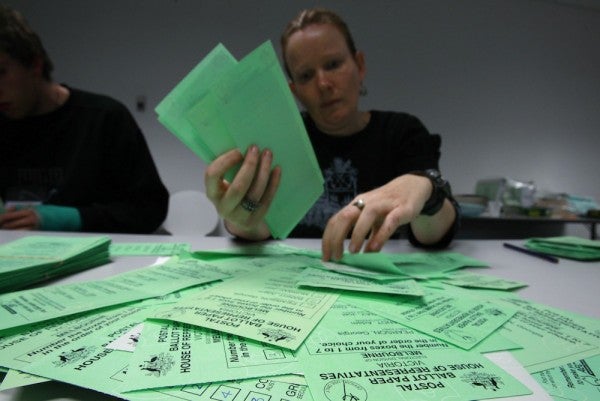

Low voter turnout has become as much a part of Los Angeles as the Dodgers and sunshine. Eric Garcetti was elected mayor this year with the votes of only 222,300 Angelenos, less than 6 percent of his city’s total population; the last time a mayor was elected with such few votes was in the 1930s, when L.A. was half the size it is today.  Now, Garcetti and City Council President Herb Wesson have proposed convening a commission to study the problem. In advance of the Zócalo/UCLA event “Why Won’t Angelenos Vote?” we asked people who work to get Southern Californians engaged in their community: What would it take to get Angelenos more involved in efforts to improve their neighborhoods and the city … and to even, um, vote in city elections?

Now, Garcetti and City Council President Herb Wesson have proposed convening a commission to study the problem. In advance of the Zócalo/UCLA event “Why Won’t Angelenos Vote?” we asked people who work to get Southern Californians engaged in their community: What would it take to get Angelenos more involved in efforts to improve their neighborhoods and the city … and to even, um, vote in city elections?

Angelenos care about L.A. When I walk precincts or engage with community residents, voters and non-voters alike can identify problems and solutions. But both problems and solutions feel too big to take on, so people prefer to either check out or place their trust in their elected officials, churches, or civic institutions. Why? Because we Angelenos feel very much on our own. Our connections to one another have been diminished by the freeways, major thoroughfares, and the land-use planning that divide us. And with our connections to each other so diminished, it’s no wonder that our connection to our government feels almost non-existent.

Fortuitously, L.A.’s massive investment in transit could lead to greater social connection, but only if we include residents at every income level in decision-making on the transit expansion. The opportunity is not the transit itself but the way it could reshape our city, concentrating new development along transit corridors and allowing us to enhance community involvement in what this new development looks like. Either we can have development that happens to be transit-adjacent, or we can have development that gets us out of cars, gets us walking, biking, and shopping locally. With the latter, we’ll be connected socially, creating a foundation for more civic engagement and opening our eyes to new possibilities for our communities.

For far too long, we have chosen to pursue a development pattern that has diminished our connection to each other and increased the time we spend in cars. We have an opportunity to build social connection by reimagining L.A. as an equitable and sustainable city where all Angelenos, regardless of their economic means, can live, work and play.

Maria Cabildo is the co-founder and president of East L.A. Community Corporation. She is a Durfee Foundation Stanton Fellow.

Voter participation in the city’s off-year municipal elections is dramatically lower than turnout in statewide elections in even-numbered years. But let’s put that in perspective: Other cities in the county also have low participation in their elections. This is true outside California, too; turnout in New York City’s recent mayoral election was only 24 percent. Low turnout often is seen when cities conduct their elections independent of statewide elections—when there’s no high-profile gubernatorial or presidential race to draw people out to the polls.

So what’s the issue here? It’s two things. First, democracy and governance are better when those who vote are representative of the population at large. We don’t have a representative voting population now, and so we ought to focus on closing the participation gap where it’s the largest. Yes, turnout in city elections is low across the board, but communities in some areas of the city, and communities with diverse demographic backgrounds, have disproportionately low voting rates.

We as a city should devote greater resources to supporting participation in these geographical areas. And we should conduct robust voter outreach efforts among underrepresented populations and address barriers that voters face on account of culture, language, and/or disability. We should also bolster civics education for young people and those eligible to naturalize—future voters—and encourage them to serve as poll workers. This will help foster interest and habitual participation in democracy.

Second, let’s look at structural changes to increase turnout, with a focus on under-participating communities; such focus makes sense because the potential to increase turnout is greatest where the participation gap is greatest. Examples include changing election dates and expanding early voting. Some structural changes may lead directly to increased turnout or indirectly so by facilitating grassroots outreach efforts. Other changes may have no effect. The new Municipal Elections Reform Commission, convened by Mayor Garcetti and Council President Wesson, will look at various proposals; city residents should provide input to inform this process.

Eugene Lee is the Voting Rights Project Director at Advancing Justice—Los Angeles, where he handles matters related to voter protection, Voting Rights Act compliance, and election policy. He has resided in the city of Los Angeles for nine years.

People don’t get involved in civic life, in large part, because they’ve gone digital—and local government’s antiquated rules of engagement were built in an analog world. Make it as easy for residents to give city hall a piece of their mind as it is to deposit a check by mobile phone, and you will see a substantial increase in civic participation—including voting. Until local government embraces online media and web-based engagement at the same levels as its constituents, the divide between governments and the public will only widen.

Local officials and their institutions can take action for stronger public engagement by experimenting with and investing in civic technology tools that provide inexpensive and accessible ways for residents to share ideas and concerns. Why drive across town to make a 3-minute statement at a council hearing when technology already exists that enables remote and real-time participation from your office or kitchen table? E-government, digital government, or government 2.0—the tools are available and the benefits are wide-ranging.

Angelenos and other Californians deserve a say in what happens in their neighborhoods and should demand a basic level of technology-driven service and engagement to ensure that their voices are heard. Employed wisely and efficiently, these tools may provide better access, better information and better results, at less of a price.

BongHwan “BH” Kim was recently selected through a national search to lead the start-up of the new Malin Burnham San Diego Center for Civic Engagement, which was founded to activate cross-sector leadership and collaboration to address complex local and regional concerns and issues. Prior to joining the San Diego Foundation, he was appointed by former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa in 2007 to serve as the General Manager for the Department of Neighborhood Empowerment (DONE), which focused on improving government responsiveness to local concerns through a citywide network of neighborhood councils.

We can begin by dispelling the notion that Angelenos are disengaged.

I see Hack for L.A., a “hackathon” convened in June where technologists created apps to make the city run better. I see Caine’s Arcade, the cardboard arcade made by a 9-year-old boy that became a viral sensation, a tourist attraction, and a foundation to inspire children who don’t have the art programs they once did. And I see Ron Finley, the “guerilla gardener” who planted vegetables in a patch of dirt between the sidewalk and the street, then fought the city for that very right—and won—in order to grow food for himself and his community in South L.A.

I see groundbreaking, backbreaking work.

Unfortunately, we have so many caring people and organizations in competition with one another for scarce resources. We need to provide coordination and support to the pioneers who have been doing this work for so long, and we need incubation for, and investment in, new tools of civic engagement that magnify the power of those individuals and organizations.

The key is to connect them.

We need hubs of nonprofit innovation that link people and organizations working on specific issues—education, poverty, violence, equal rights, and the environment—to draw from the best of the existing work in town. Then we should match those hubs with media producers and digital strategists so that they can grow their audiences. When aligned, our interests become common, and we can solve enormous problems.

The city also needs to show more faith in its citizens.

If we shift our spending priorities from law enforcement, incarceration, and narrow models of development to investment in education, community-based intervention, and reduction of the income inequality that divides us, we will see a return across all bottom lines.

And if voter turnout is low, don’t move the voters. Move the election.

Shift citywide elections back a few months so they happen at the same time as our statewide elections. Turnout will soar, and we will see that our neighborhoods, our city, our state, and our nation are bound together by the ballot, and then by belief.

Adam Vine runs Wake the Beast, an L.A.-based social action studio that creates media for campaigns and nonprofits.

The way Los Angeles conducts its elections depresses voter turnout, makes campaigning expensive, and limits political representation and voter choice in three ways.

1. Holding stand-alone spring elections is a major reason why L.A.’s turnout is so low. Such separate local elections have only a small number of contests to draw voters. When local elections are scheduled on the same day as statewide or presidential, those higher office races increase voter interest—and also increase the number of campaigns who are working to get out the vote.

L.A. only has to look next door to see the advantages of shifting the election calendar. Thirty years ago, the city of Santa Monica changed from spring municipal elections to consolidating them with November general elections in even-numbered years. Turnout rose immediately, doubling (and in some elections almost tripling) what it had been before.

2. L.A.’s system of runoff elections—with a first round in March and a runoff among the top two candidates in May—results in more negative campaigning, because it’s easiest to defeat your opponent in a runoff by knocking them down. Runoffs also cost more—both for the taxpayer (who has to pay for two elections) and for the candidate (who has to pay for two different races). That means more fundraising is required of would-be officeholders, thus increasing the influence of big money in politics.

As an alternative, L.A. should embrace Ranked Choice Voting (RCV), which is being used in Oakland, San Francisco, and other cities across the county. RCV allows voters to focus on one election, and turn out only once to be heard. Voters rank candidates in their order of preference. If no candidate wins an outright majority of first choices, the rankings allow simulation of a series of runoffs, with the last-place finisher eliminated and votes for them added to each ballot’s next choice until one candidate wins a majority. Under RCV, candidates may need the second or third rankings from the supporters of others to reach a majority, so they have an incentive to speak to the issues, build coalitions and find common ground, rather than tear one another down—the very opposite of what happens in L.A.

3. L.A. has the largest city council districts by population in the country by far–which means its residents, on a per capita basis, have less representation at the city council level than other Americans. Substantially increasing the number of council seats would improve representation and make it easier for the legislative body to reflect the city’s diversity. The resulting smaller, less populous districts would make it less expensive to run, and would give more voice to neighborhoods and community groups.

Michael Feinstein is a former mayor and city councilmember in Santa Monica. He is currently a spokesperson for the Green Party of California and is on the activist advisory board for Fairvote, a national organization in the U.S. focused on electoral reform.